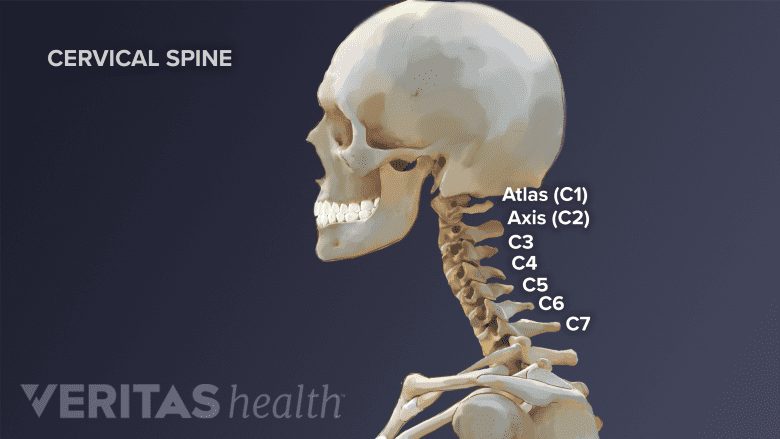

Seven cervical vertebrae, labeled C1 to C7, form the cervical spine from the base of the skull down to the top of the shoulders. At each level, the cervical vertebrae protect the spinal cord and work with muscles, tendons, ligaments, and joints to provide a combination of support, structure, and flexibility to the neck.

There are some differences among the cervical vertebrae. The vertebrae at the top of the neck tend to be smaller and more mobile while the lower cervical vertebrae are larger to handle greater loads from the neck and head above.

In This Article:

Typical Cervical Vertebrae: C3, C4, C5, and C6

C3, C4, C5, and C6 cervical vertebrae share characteristics with most of the vertebrae throughout the spine.

Cervical vertebrae C3 through C6 are known as typical vertebrae because they share the same basic characteristics with most of the vertebrae throughout the rest of the spine. Typical vertebrae have:

- Vertebral body. This thick bone is cylindrical-shaped and located at the front of the vertebra. The vertebral body carries most of the load for a vertebra. At most levels of the spine, an intervertebral disc sits between 2 vertebral bodies to provide cushioning and help absorb the shock of everyday movements.

- Vertebral arch. This bony arch wraps around the spinal cord toward the back of the spine and consists of 2 pedicles and 2 laminae. The pedicles connect with the vertebral body in the front, and the laminae transition into the spinous process (a bony hump) in the back of the vertebra.

- Facet joints. Each vertebra has a pair of facet joints, also known as zygapophysial joints. These joints, located between the pedicle and lamina on each side of the vertebral arch, are lined with smooth cartilage to enable limited movement between 2 vertebrae. Spinal degeneration or injury to the facet joints are among the most common causes of chronic neck pain.

Watch Spinal Motion Segment: C2-C5 Animation

The small ranges of motion between the 2 vertebrae can add up to significant ranges of motion for the entire cervical spine in terms of rotation, forward/backward, and side bending.

Atypical Cervical Vertebrae: C1 and C2

C1 (atlas) and C2 (axis) allow the head to rotate.

C1 and C2 are considered atypical vertebrae because they have some distinguishing features compared to the rest of the cervical spine.

- C1 Vertebra (the atlas). The top vertebra, called the atlas, is the only cervical vertebra without a vertebral body. Instead, it is shaped more like a ring. The atlas connects to the occipital bone above to support the base of the skull and form the atlanto-occipital joint. More of the head’s forward/backward range of motion occurs at this joint compared to any other spinal joint.1Heinking KP, Kappler RE. Cervical region. In: Chila A, ed. Foundations of Osteopathic Medicine. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkens. 2010: 513-527.,2Hartman J. Anatomy and clinical significance of the uncinate process and uncovertebral joint: A comprehensive review. Clinical Anatomy. 2014; 27(3):431-40.

- C2 Vertebra (the axis). The second vertebra, called the axis, has a large bony protrusion (the odontoid process) that points up from its vertebral body and fits into the ring-shaped atlas above it. The atlas is able to rotate around the axis, forming the atlantoaxial joint. More rotational range of motion occurs at this joint compared to any other, with some estimates being that nearly half of the head’s rotation occurs at this joint.1Heinking KP, Kappler RE. Cervical region. In: Chila A, ed. Foundations of Osteopathic Medicine. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkens. 2010: 513-527.,2Hartman J. Anatomy and clinical significance of the uncinate process and uncovertebral joint: A comprehensive review. Clinical Anatomy. 2014; 27(3):431-40.

Watch C1-C2 (Atlantoaxial Joint) Animation

While C1 and C2 are the smallest of the cervical vertebrae, they also are the most mobile.

The Unique Cervical Vertebra: C7

The C7-T1 spinal segment connects the cervical spine in the neck to the thoracic spine in the upper back.

The seventh cervical vertebra, also called the vertebra prominens, is commonly considered a unique vertebra and has the most prominent spinous process. When feeling the back of the neck, the C7 vertebra’s spinous process (bony hump) sticks out more than the other cervical vertebrae.

C7 is the bottom of the cervical spine and connects with the top of the thoracic spine, T1, to form the cervicothoracic junction—also referred to as C7-T1. Not only is C7’s spinous process significantly bigger than those of the vertebrae above, it is also a different shape to better fit with T1 below. C7 also lacks holes (foramina in its transverse processes) for vertebral arteries to pass, which are present in all of the other cervical vertebrae.

Watch Spinal Motion Segment: C7-T1 (Cervicothoracic Junction) Animation

Due to its larger size and key location at the cervicothoracic junction, more muscles connect to C7’s spinous process compared to other cervical vertebrae.

Uncovertebral Joints: Special Joints Between C3-C7

By age 10, uncovertebral joints are formed between C3-C7 vertebrae.

The uncovertebral joints, also called Luschka’s joints, are found between vertebral segments from C3 down to C7. These joints are comprised of two uncinate processes—one rising from the top of each side of the vertebral body—that fit in indentations in the vertebral body above. They help with the neck’s forward and backward movements while also limiting the bending to either side.

Compared to the facet joints, the uncovertebral joints are relatively small and not present at birth. The uncovertebral joints typically develop by age 10.2Hartman J. Anatomy and clinical significance of the uncinate process and uncovertebral joint: A comprehensive review. Clinical Anatomy. 2014; 27(3):431-40. The uncovertebral joints are also a common location for bone spurs (osteophytes) to develop as the spine ages, which can eventually compress a nearby spinal nerve.

While the vertebrae provide the neck with stability and protection, these bones are held together and supported by soft tissues as discussed on the next page.

- 1 Heinking KP, Kappler RE. Cervical region. In: Chila A, ed. Foundations of Osteopathic Medicine. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkens. 2010: 513-527.

- 2 Hartman J. Anatomy and clinical significance of the uncinate process and uncovertebral joint: A comprehensive review. Clinical Anatomy. 2014; 27(3):431-40.