If scoliosis continues to get worse and bracing is either not feasible or not working for the patient, surgery may be considered.

In This Article:

3 Goals of Scoliosis Surgery

Scoliosis surgery typically has the following goals:

- Stop the curve’s progression. When scoliosis requires surgery, it is usually because the deformity is continuing to worsen. Therefore, scoliosis surgery should at the very least prevent the curve from getting any worse.

- Reduce the deformity. Depending on how much flexibility is still in the spine, scoliosis surgery can often de-rotate the abnormal spinal twisting in addition to correcting the lateral curve by about 50% to 70%. These changes can help the person stand up straighter and reduce the rib hump in the back.

- Maintain trunk balance. For any changes made to the spine’s positioning, the surgeon will also take into account overall trunk balance by trying to maintain as much of the spine’s natural front/back (lordosis/kyphosis) curvature while also keeping the hips and legs as even as possible.

See Scoliosis Surgery: Potential Risks and Complications

In addition, any adjustment of the spine must also consider the possible effect on the spinal cord. The health of the spinal cord must be monitored throughout the surgery.

Surgical Options for Idiopathic Scoliosis

Spinal fusion aims to eliminate movement between vertebrae to achieve curvature correction.

There are 3 general categories of scoliosis surgery:

-

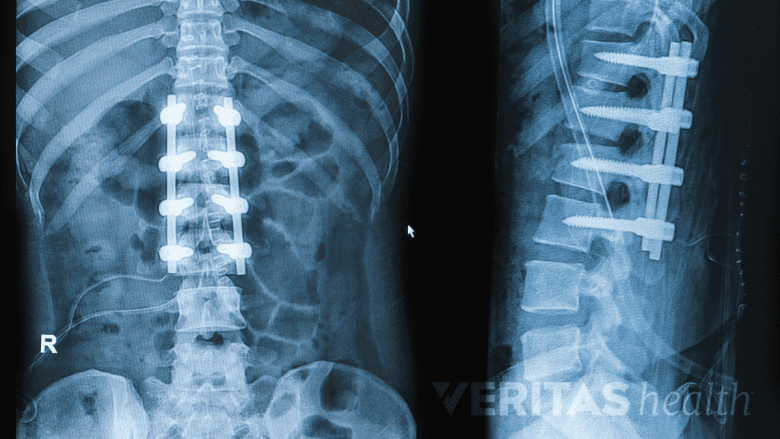

Fusion. This spinal surgery permanently fuses two or more adjacent vertebrae so that they grow together at the spinal joint and form a solid bone that no longer moves. Modern surgical approaches and instrumentation—rods, screws, hooks, and/or wires placed in the spine—have enabled spinal fusion surgeries to achieve better curvature correction and faster recovery times than in the past.

See Lumbar Spinal Fusion Surgery

An advantage to spinal fusion surgery is that it has a long-term record of safety and efficacy for treating scoliosis. While a drawback to the procedure is that any fused vertebrae will lose mobility, which can limit some of the back’s bending and twisting, today’s spinal fusions tend to fuse fewer vertebrae and maintain more mobility than in the past.

-

Growing systems (to delay fusion). Rods are anchored to the spine to help correct/maintain the spine’s curvature while the child grows. Every 6 to 12 months, the child has another surgery to lengthen the rods to keep up with the spine’s growth. Once the patient is close enough to skeletal maturity, the patient will usually get a spinal fusion.

Fusionless. Current fusionless surgery methods employ growth modulation on the spine similar to what has been done in the past to treat unequal leg heights in growing children. The theory is that by putting constant pressure on a bone, it will grow slower and denser. By applying such pressure on the outer side of a spinal curve, the surgeon aims to slow or stop the growth of the curve’s outer side while the curve’s inner side continues to grow normally. As the spine continues to grow in this manner, the lateral curvature should reduce as the spine becomes straighter.

One fusionless method uses a vertebral tethering system, which involves placing screws on the outer side of the curve and then pulling them taut with a cord so the spine straightens. Compared to spinal fusion, fusionless surgery has the potential benefit of retaining more spinal mobility. However, this is a newer approach and long-term data about the risks and benefits are not yet available.

For an adolescent or young adult opting for scoliosis surgery today, by far the most commonly performed surgery is a spinal fusion.

See Long-Term Outlook for Adolescents Who Have Scoliosis Surgery